VOGEL STROVE TO BREAK DOWN BARRIERS

Role model for China scholars showed broad vision

When 28-year-old Ezra Vogel completed his PhD in sociology at Harvard University in 1958, his thesis was on family and mental health in the United States.

His studies had nothing to do with East Asia, an area for which he later became a top scholar.

After he graduated, Vogel went to Japan in 1958, where he stayed for two years to study the language and do fieldwork to gauge whether his research was applicable in another culture.

After renowned China scholar John Fairbank called him in 1961 about studying the Chinese language and history on a three-year scholarship, Vogel seized the opportunity immediately.

"I didn't seek it. I was given the opportunity," he told me in an interview in October 2011 at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

For more than 60 years, China and Japan were his keen focus of study, and he was deeply worried about the often strained relations between the two countries.

"In the future, it's very necessary for China and Japan to get along, and I know that World War II was one of the biggest problems interfering with their ability to get along. I think I have a special responsibility and opportunity because I know both China and Japan," he said during the interview.

Speaking, reading and writing both Chinese and Japanese, Vogel hoped that the two countries would strive to build trust and friendship. As a scholar, he thought he was unable to play a role like political leaders in making major decisions, but that he could contribute to increasing understanding between Beijing and Tokyo.

In a talk held by the National Committee on US-China Relations that I attended in New York on Feb 18, 2015, Vogel, who was about to turn 85, said that if his energy and health permitted, he wanted to write a book on Sino-Japanese relations.

By then, he had organized numerous conferences for Chinese, Japanese and Western scholars to examine the 1937-45 war, known in China as the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45).

He thought that his books, which received rave reviews in China and Japan, won him trust in both countries.

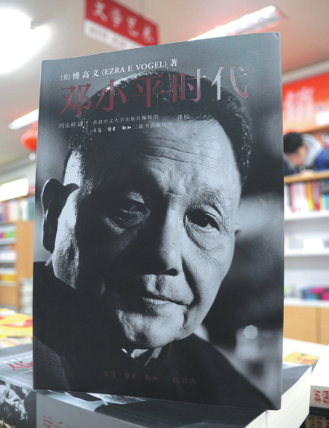

The Japanese edition of his book Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, published in 1979, was an alltime best-seller in Japan for a work of nonfiction by a Western author, while the Chinese edition of his work Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, published in 2011, was a best-seller in China.

His earlier books had been aimed at US readers, but his most recent work was largely intended for Chinese and Japanese readers.

China and Japan: Facing History, published in July last year, was his last book. In it, Vogel talked about the 1,500-year history of the two countries learning from each other.

He argued that Japan should offer a thorough apology for the atrocities it committed in World War II, while urging China to recognize a totally transformed Japan after the war. He also called on the two neighbors to reset their relationship for the sake of a stable region and world.

"I have many friends in Japan, I want Japan to succeed. I have many friends in China, I want China to succeed," Vogel said during a talk at a book promotion in Hong Kong on Nov 11 last year.

In the 2011 interview, he praised former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping for doing "very good things" in the 1980s to improve relations with Japan.

"He tried to introduce Japanese movies, television and novels-literature of all kinds," Vogel said, adding that Deng learned a lot from Japan on how to modernize industry, improve quality control and be efficient.

Vogel also heaped praise on late Chinese leader Hu Yaobang for promoting a healthy relationship and cultural exchanges with Japan.

Sadly, Vogel was unable to finish his book on Hu, which he had been working on for six years before his death on Dec 20 at age 90.

In the 2016 Chinese edition of his book Japan as Number One, Vogel, known to many in China by the name Fu Gaoyi, expressed concern in the preface that some of his Chinese friends felt that their country had nothing more to learn from Japan now that the Chinese economy has eclipsed that of Japan.

He noted that Japan still outperformed China in a number of areas, such as having a relatively small income disparity, low corruption levels, high product quality, a universal and reasonably priced healthcare system, low crime rate, public civility, clean cities and an orderly and trust-based society.

Most important book

Vogel wrote many books, but his work on Deng took him the longest-10 years-to complete. He read books about Deng, traveled to China numerous times and interviewed hundreds of influential Chinese figures and foreigners.

It was the most important book he had written, he said in the 2011 interview.

"Deng made more contributions to China than any other leader in the 20th century because he put the country on a path to the future," Vogel said, adding that he admired Deng personally.

"China was so lucky to have such a leader to bring such progress," he said.

Vogel said that in 1978, nobody in the West imagined that the Chinese Communist Party could lead a country to grow faster than capitalist nations. "Even scholars had no idea," he said.

He pointed out that while China's success offered much for others, especially developing countries, to learn from, there was no set model.

"Deng was very smart. He didn't exactly have a model. He wanted to learn the best things from everywhere and adapt (them) to the needs of his own country," Vogel told China Daily, adding that every country should do this.

He believed it was no accident that Deng was a capable and pragmatic leader, given the many ups and downs he experienced. Deng had "seen so much, thought so much and had always been around," he said.

In his view, Deng had a vast range of governance experience to draw on at local, regional and national levels.

In his later public talks, Vogel told audiences that Chinese officials were well trained, given their experience of working at various levels. He taught and spoke to some of them when they visited Harvard for training courses.

China-US ties

Vogel lamented that officials in the current US administration knew far less about China compared with their Chinese counterparts' knowledge of the US. He worried about the deteriorating relations between the two countries over the past three years.

"The idea of decoupling is impossible and won't go very far," he said during the talk in Hong Kong in November last year.

On July 3 last year, Vogel and several other China experts published a joint letter in The Washington Post titled "China is not an enemy".

Signed by some 100 China scholars, business leaders and foreign policy experts, the letter argued that the deterioration of bilateral relations did not serve US or global interests, and said many US actions were contributing directly to the downward spiral in ties. Seven proposals were put forward to improve relations between the two countries.

In an op-ed article in The Washington Post on July 22, Vogel argued that "US policies are pushing our friends in China toward anti-American nationalism".

He wrote that US policy and political rhetoric toward China in recent years had been dominated by officials with limited knowledge of developments in China.

"It is not in the United States' interest to turn the Chinese into enemies," he wrote, adding, "We need some fundamental rethinking of our policies."

In a talk at the China Institute in New York on Sept 17 last year, Vogel urged people to do whatever they could to prevent a new Cold War between the two countries. More than a year ahead of the US presidential election, he said he hoped the new administration would "reverse the course".

Vogel was well received by many Chinese scholars when he attended the virtual Xiangshan Forum early in the morning US Eastern Standard Time on Dec 1, when he shared his views on how to improve relations during the upcoming administration of Joe Biden.

Nixon memorandum

Born to a Jewish family in Delaware, Ohio, on July 11,1930, Vogel graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in the small college town in 1950, with no knowledge of East Asia.

However, on Nov 6, 1968, when he was a Harvard professor of social relations, he was among a small group of scholars from that university, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Columbia University who wrote a memorandum to US president-elect Richard Nixon, asking him to review hostile US policy toward China.

Nixon had hinted before the presidential election of establishing a new relationship with the People's Republic of China, but it was several years before National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, a former colleague of Vogel and others at Harvard, made his secret visit to China in July 1971.

John Fairbank and other top China scholars such as Lucian Pye, A. Doak Barnett, Dwight Perkins and Jerome Cohen were among the signatories of the memorandum.

In the 1960s, when traveling to the Chinese mainland was impossible for US citizens, Vogel spent a year in Hong Kong in 1963. He interviewed Chinese arriving in the city from across the border. At the time, Hong Kong was under British colonial rule.

He made his first trip to the mainland in May 1973 with a delegation from the US National Academy of Sciences, during which they met Premier Zhou Enlai and other high officials.

The fact that he never had the chance to meet and talk with Deng in person remained a source of regret for Vogel. Their closest contact was on Jan 30, 1979, during a reception at the National Gallery in Washington, where Deng made a speech during an official visit to the US.

Vogel, who spent almost his entire career teaching at Harvard until his retirement in 2000, visited China at least once or twice a year since 1980. That year, he spent two months at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province. Seven years later, he spent seven months in that province.

For his book on Deng, he spent seven months in Beijing, Shanghai and other areas of China.

I interviewed Vogel many times. For the first few articles, he surprised me by asking to read them before they were published, to ensure he was quoted accurately.

However, he never asked for any changes. In one typical email, he wrote, "Dear Weihua, You quoted me accurately, and I liked your article. I appreciate your sending it to me. I am pleased to cooperate with journalists when they report me accurately. Ezra Vogel."

I last saw Vogel in late March 2018 at the Association of Asian Studies Annual Conference at the Marriott Wardman Park Hotel just across the street from my apartment in Washington. It was about 10 weeks before I completed my posting in the US.

I was walking toward the hotel room of Thomas Rawski, a leading scholar on the Chinese economy at the University of Pittsburgh, for an interview appointment when a door I was passing suddenly opened.

There stood Vogel, looking at me with a kind smile and offering greetings.

chenweihua@chinadaily.com.cn