In search of DEAN LUNG, a Chinese person

Recently surfaced correspondence heightens the intrigue over the identity of a man who has had pride of place in a US university for nearly 120 years

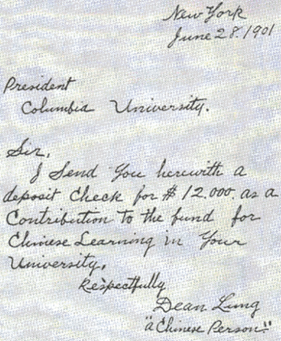

"I send you herewith a deposit check for $12,000 as a contribution to the fund for Chinese learning in your university," a Chinese manservant named Dean Lung wrote in a letter to Seth Low, president of Columbia University in New York 119 years ago.

Today a giant picture of the donor, based on one of the two known archival images of him, adorns Kent Hall, the building that houses the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, a department his generosity helped found.

Yet despite the prominence the department enjoys in its field of learning in the US and elsewhere, Dean Lung remains an enigma, in the minds of many a mere shadow of the glory he helped mint.

On April 14 Huang Xiangguang, a magazine editor in Taishan county, Guangdong province, was awoken at midnight by his ringing phone.

"It was my brother Huang Xianghuo, who is in Ashland, Ohio," Huang says.

"He sent me scanned copies of two letters-one in Chinese, another in English-with a note saying Dean Lung was in fact Ma Wanchang, the maternal great-grandfather of one of his former classmates from Taishan, Huang Changming, who now lives in New York."

Sensing that this matter was urgent, Huang Xiangguang, then out of town, returned to Taishan the next day, looking for traces left by Ma in the small village that he once lived in and that makes up part of the county.

There, it seems, Ma had enjoyed a certain notoriety among older people, who almost certainly would have heard about him through now-dead villagers. In that telling of the story Ma is depicted as an expatriate who had traveled to the United States and made a fortune before eventually returning home, where he would spend the rest of his life. His tomb sits at the foot of a mountain in the village's south, while his descendants are scattered in China and North America.

Chen Jiaji, a Guangdong native who became interested in the story of Dean Lung after watching a TV documentary in 2009, was among the first to see the letters.

"I spent most of the past 10 years in South Africa and returned to Guangzhou late last year and have been there since because of the COVID-19 outbreak," he says.

With a lot of spare time suddenly available, Chen decided to revisit his old interest and joined an online group formed by him, Huang Xiangguang and a number of others. They call it the Dean Lung Search Team.

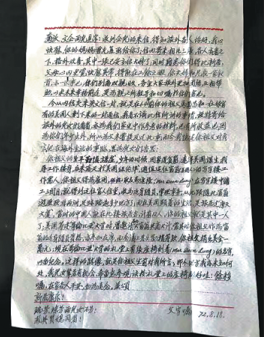

The Chinese letter is believed to have been penned in Taishan by Ma Weishuo, the son of Ma Wanchang, to his own two sons in the US.

"When he was young, your grandfather was driven by poverty to seek his fortune in the United States," says the letter, written entirely in traditional Chinese, with one exception. "He eventually set foot in New York and entered the employment of a rich American. He gave himself a new name, Ma Jinlong-Mar Dean Lung."

The writer had taken the trouble to spell out his father's late-acquired name both in Chinese (Ma Jinlong) and in English (Mar Dean Lung). Ma Jinlong is the Chinese name's spelling in pinyin, the phonetic symbols used for the romanization of Chinese characters, adopted by the Chinese mainland in the 1950s.

Among other details, Ma Weishuo went on to talk about the donation of $10,000 to Columbia University by his father, and a chair in which the name "Mar Dean Lung" is carved that can be found in the university auditorium.

A few lines earlier Ma Weishuo wrote:"Accompanying my words is an English letter-what has remained of the correspondence between your grandfather and that rich American. Since I don't know what it is talking about, I'm sending it to you."

The letter was dated August 18,1972, a few years before Ma Weishuo moved to New York from Taishan to join his two sons, Ma Tengwo and his younger brother Ma Wenqi, the father of Karen Yin Ma, the current holder of the letters. Karen Ma provided copies of the letters to her paternal cousin Huang Changmin, who then sent them to his former classmate Huang Xianghuo.

The unexpected appearance of the letters delighted members of the Dean Lung Search Team. Pictures of another English letter and an envelope followed a week later, again from Karen Ma.

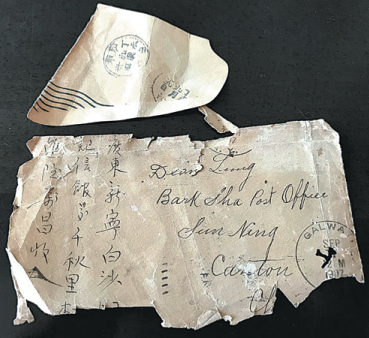

Both the English letters and the envelope, which Chen believes held one of the letters, were sent by a man named Horace Walpole Carpentier from Galway, New York state, to Dean Lung in China.

The envelope has on it the delivery details, including the name of the addressee, in both English and Chinese. The English reads "Dean Lung, Bark Sha Post Office, Sun Ning, Canton, China". Sun Ning is the old name for Taishan and Canton is the old English name for Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong.

The Chinese characters on the envelope, in three vertically lines, state the addressee as Jin Long Wan Chang. Jin Long and Dean Lung are pronounced in a similar way. Thus two seemingly unrelated names-one associated with Columbia University but unable to ring any bell in this part of China, the other vividly recalled by seniors in the village yet totally unheard of outside of it-are linked.

"Carpentier was Dean Lung's employer and patron," the rich American" Ma Shichou mentioned in his letter", says Chen Jiaji, who has searched between the lines for information that could shed precious light on two ill-defined figures, as well as a relationship that is probably mind-changing for both.

"The year on the envelope is a clear, stamped 1907. Although the year handwritten on one of the letters appears to be 1917, I now believe that both were actually written in 1907, judging by the letters' contents,"Chen says. (The other letter's dateline does not include the year.)

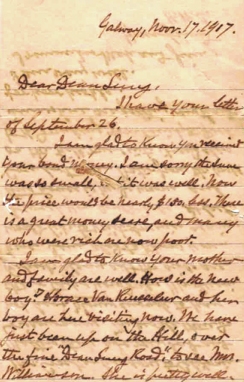

One thing that is palpable is the sense of attachment Carpentier felt to Dean Lung.

In one letter, dated Sept 17, Carpentier wrote,"I have now more land than I want or can take care of. We are alone… Try to come and see me once more."

In the other, dated Nov 17, Carpentier wrote: "I am glad to know that you would like to visit America again. I wish you could do so."

"The second letter clearly indicates that Dean wrote back upon receiving the first one," Chen says. "In fact, Carpentier must have written Dean Lung another letter in August because in that letter in September he talked about 'my letter of August 4'." Both were signed "Your friend, H.W.C.".

In 1901, 20 days before Dean Lung made his donation to Columbia, Carpentier gave $100,000 to the university, with a letter to Seth Low dated June 8.

"For 50 years and more I have been saving something from whisky and tobacco bills which with fair interest would amount perhaps to the sum of the enclosed check, which I have pleasure to send you toward the founding of a department of Chinese languages, literature, religion and law, to be known as Dean Lung professorship of Chinese," the letter said.

And it is worth noting that a letter and check that Dean Lung sent to Low on June 28 was enclosed within another letter of Carpentier to Low, written the same day, in which Carpentier suggested that the university provide "a life annuity" for Dean Lung since he "is a man of modest means" and therefore "ought not to give so much outright to any public object".

This correspondence is now kept in the Columbia University archives.

Mia Anderer, editor, freelance proofreader and researcher, was first drawn to the story of Dean Lung 15 years ago when her husband Paul Anderer, then Vice Provost for International Relations at Columbia, wanted to rename the Kent Hall "Dean Lung Hall". Mia Anderer has been in contact with Karen Ma since mid-April, the latter having contacted Paul Anderer by email.

"Karen's letters are convincing," she says. "Of the two English letters, the November one (with the year 1917) is written in Carpentier's very distinct handwriting while the other I believe was penned by Caroline Crocker, a household assistant who routinely helped him with his correspondence."

Over the years Mia Anderer has plowed deep into the archives of Columbia University and Barnard College, also in New York, to both of which Carpentier bequeathed his house in Manhattan and all its contents. Other sources include federal and local census reports, immigration papers, shipping records as well as books, recollections and oral history.

Of all, it is a few lines from Dean Lung himself, written as a sworn affidavit on his return to the US from China in 1899, that draws a hasty sketch of the man: "Dean Lung 5 ft 7 in. 41 years old. Res. 108 E. 37 St. New York… When I first came to U.S. I landed in San Francisco, remain there about 1 year at Mission St. then came to New York when 18 yr. old".

A lot of information can be gleamed from and therefore verified by other sources. According to the 1900 US Federal Census Report, Dean Lung was born in 1857 and first came to the US in 1875. (It is in this report that Dean Lung appears for the first time as a member of the Carpentier household, under the address of 108 East, 37th Street, New York.

Following his donation, Dean Lung also appeared in a New York Tribune article that said:"He was 16 years old when Mr. Carpentier engaged him at San Francisco to do light work, and he has been in his employment constantly since that time."

In all likelihood, the man known as Dean Lung traveled to the US west coast following the footsteps of his compatriots, 27 years after gold was discovered in California and six years after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad linking America's west with its east, half of which was built by Chinese immigrant laborers.

There he met Carpentier, 33 years his senior, who had sought and found his fortune in California, after graduating from Columbia.

Equipped with vision and entrepreneurial streak, Carpentier presided over the construction of the western portion of the transcontinental telegraph, and launched ferry services between San Francisco and Oakland.

Yet the daring man was equally known for his utter lack of scruples paired with coldblooded cunning when it came to accumulating wealth at the expense of others or the public.

In 1852 Carpentier persuaded the new California state legislature to incorporate Oakland as a town. Days later the new town's trustees passed an ordinance that in effect gave him complete, lucrative control of Oakland's waterfront to Carpentier. This was discovered in 1855, a year after Carpentier had been elected Oakland's first mayor.

Anderer says it is believed that from 1888 Carpentier lived mainly in New York, having "left Oakland for good in 1868". Apart from the building at 108 East 37th Street in Manhattan, he maintained two summer homes in Galway, a small town in Saratoga county, about 280 kilometers north of New York.

A thoroughfare connecting the two homes in Galway "was built at Carpentier's expense through what was formerly swamp land", Anderer says, and was named Dean Lung Road.

A potent reminder of the good old days, the road was mentioned in both of Carpentier's letters to Dean Lung as provided by Karen Ma.

The road still exists. Between 2006 and 2009, Anderer visited Galway twice and has been in contact with several local historians.

"Dean Lung is remembered as a quiet man who was kind to the neighbors and the children in the area," she says. "He often went to the train station to meet guests and would shop at the village store, frequently ordering oysters and clams."

Anderer believes that in some "apocryphal stories" Dean Lung is confused with another of Carpentier's Chinese servants, Mah Jim. Both must have constituted a striking presence in that small town.

"For this research to continue, it will be imperative that we find his real name in Chinese with Chinese characters," Anderer wrote in 2006.

It was not until 2017 that contact was established between her and a group of Dean Lung researchers in China. Chen Xiaoping, a history buff who once owned a bookstore next-door to Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, is a devoted member of that group.

In February last year he came across a digitized copy of the China West Daily, or Chung Sai Yat Po, a Chinese newspaper published in San Francisco between 1900 and 1951. On August 21, 1901, the paper carried a report on Carpentier's donation to Columbia to honor his long-time helper, in which Dean Lung appeared under the Chinese name Jin Long, written using the same two characters that appeared on the envelope purported to have been sent by Carpentier to Dean Lung, and in Ma Weishuo's 1972 letter to his sons reminding them of their grandfather's legacy.

"In Taishan dialect the specific Chinese character written as jin in pinyin is indeed pronounced 'dean'," he says."Given that the founder of the newspaper, Ng Poon Chew, hailed from Taishan, this is probably the correct Chinese name for the man identified elsewhere as Dean Lung.

"I have long suspected that Dean Lung, whatever his real name is, might have been from Taishan, or Sun-ning, for the simple reason that back then, Taishan natives accounted for half of all Chinese immigrants in America."

Chen Xiaoping's suspicion was bolstered when a Chinese reporter working on a Dean Lung documentary series in the US encountered crucial evidence in Yale University archives last summer.

There, in the archives of Lingnan University, formerly known as Canton Christian College, was a letter written in May 1913 by a Mr Henry Grant to Dr. Andrew H. Woods, acting president of the college in what is now Guangzhou, to which Carpentier had donated generously.

The letter begins: "Mr. Paget and I have just been for a call on Mr. W. H. Carpentier, 108 East 37th Street. He seems very much disappointed that you have not managed to get Mah Chung Dean, a boy of 16 years of age, living in Sun-ning, whose father Mah Jim is one of his personal attendants."

Chen Xiaoping offers this interpretation:"Grant worked for the foundation of the college in New York, and it is clear, based on this and other letters that Carpentier was trying to bring Mah Jim's son to New York from his hometown in Sun-ning, with the help of Woods.

"Keeping in mind the striking parallelism of the life trajectories of Dean Lung and Mah Jim, I have enough reasons to believe that they came from the same place, knew each other back in China and together embarked on their initial journey to the US."

Together with Dean Lung, Mah Jim is also listed in the 1900 US Federal Census in the Carpentier household as a cook, born in 1855 (two years older than Dean Lung) and having immigrated, like him, in 1875.

One year after Dean Lung and Carpentier made their donations, Mah Jim also contributed $1,000 to the Dean Lung Fund.

"In the 19th century it was very common for men from the same village to share one ancestor and thus one surname," Chen Xiaoping says. If Mah Jim's family name is Mah, then there is a possibility that Dean Lung is also surnamed Mah."

Or Mar, since both are among a number of English variants for a particular Chinese character written in pinyin as ma.

According to paperwork, Dean Lung left New York on June 27, 1905. The last reference to him that Anderer has found is in a letter written by Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Bulter, Low's successor, to Carpentier on December 27, 1906.

"Thank you for letting us know that Dean Lung and Mah Jim are now in China…" Bulter wrote. While Mah Jim latter appeared in the 1910 US Federal Census and the 1915 New York State Census, Dean Lung disappears from US official documents after this.

Many believed him dead, including Bronson Taylor, a life-long resident of Galway who had occasion to speak with Carpentier. In his book Stories and Pictures of Galway, the author says unequivocally that "Dean Lung is buried in the Carpentier lot in Barkersville Cemetery".

Anderer, for her part, has been convinced by ample evidence to reject that view. There is no death record of Dean Lung in Galway or the rest of New York state.

"I know that is not true (that Dean Lung died in the US) because he is my great-grandfather," wrote Karen Ma in an article titled From Zero to Hero in which she traces the passing-down from one generation to another of a much-treasured family story.

"The first time my father mentioned my great-grandfather was when my dad told us we should go look for a chair in Columbia University dedicated to my great-grandfather for his financial donation. We imagined it was a wooden chair with a copper plate that had his name engraved on it," she wrote, in an echo to Ma Weishuo's letter in which he asked his sons to look for that chair.

"I finally visited Columbia University in November 2019 … By this time I had figured out that the chair was not a piece of furniture but rather a position that the endowment funded," she said in the article.

Another person who has heard the story, directly from Ma Weishuo, is Huang Changquan, elder brother of Huang Changming.

"In the late 1960s and early 70s, while most of my family were in the States, I was in Taishan with my parents and maternal grandparents," says Huang Changquan, whose mother was Ma Weishuo's eldest child and so Karen Ma's eldest aunt.

"For some time I lived on the second floor of my grandparents' house, built by Dean Lung after he returned to China permanently."

Huang Changquan recalls helping his grandparents with the disposal of some moldy carpets long-stored in the building's attic.

"They told me that my great-grandfather bought all those carpets and decorated the building's floor, when Carpentier, who was in Hong Kong, probably in the late 1900s, wrote to say that he was planning to visit his old friend in his home. Carpentier eventually didn't come, and Taishan, hot and humid, was certainly not the best place for those fluffy carpets."

According to Huang Changquan, Dean Lung, or Grandpa Wanchang as his mother knew him, was a kind gentleman who took his granddaughter on trips to as far as Hong Kong, and as near as the county seat of Taishan, where there was a newly built railway.

"They didn't have to pay for the train ticket because my great-grandfather owned shares in the railway. 'Where does your money come from?' my mother would ask. And that's when he started to talk about his days working for that rich American."

"I believe my great-grandfather had decided not to go back to the US mainly because of the birth of his son Ma Weishuo. In light of local tradition, he had married before he headed for the US in 1875, probably at the age of 18. But it was not until 1907, when he turned 50, that he finally got his first biological son," says Huang Changquan, who points out that before Weishuo, his great-grandfather had adopted a son, in the hope of "prompting the arrival of another son", an idea deeply rooted in local superstition.

In his letter to Dean Lung dated Nov 17, Carpentier wrote: "I am glad to know your mother and family are well. How is the new boy?" According to old family genealogy records kept by one of Ma Wanchang's offspring, Ma Weishuo was born around April 1907. Among other things, this has led Anderer to conclude that the letter was indeed penned in 1907 instead of 1917.

According to the same records, Ma Wanchang was born in 1857, the same year written for Dean Lung on the 1900 US Federal Census form. He died in 1936, one year before Japan invaded China.

By the time Carpentier died in 1918 he had donated more than $210,000 to the Dean Lung Fund of Columbia University.

Reflecting on the latest development to the ever-evolving Dean Lung story, Chen Xiaoping says he believes in the authenticity of the two Carpentier letters that Karen Ma holds but is more willing to give the benefit of doubt to the proposition that Dean Lung is Ma Wanchang, if even he is indeed surnamed Ma (Mar).

"One thing that particularly baffles me is that Dean Lung would ask his posterity to go and look for a chair at Columbia University, not knowing that the Dean Lung Chair is an honored teaching position to be occupied by a revered scholar of Chinese learning. Carpentier must have made it very clear to him, and Dean Lung, smart enough to win the trust of an eccentric and demanding man, must have understood it."

There are disparities between what Ma Weishuo's letter talks of and what Chen Xiaoping believes must have happened to Dean Lung. For example, the letter tells of Carpentier recruiting Dean Lung in New York, whereas most other sources say this happened in California.

Chen also points to the fact that when Carpentier tried to bring Mah Jim's son to the US around 1913, he enlisted the help of the president of Canton Christian College instead of Dean Lung, who would seem to have been an obvious choice if he had been in China and alive at the time.

However, Chen believes Carpentier could have miswritten 1907 as 1917 because he was known for making similar mistakes on other occasions.

"If Dean Lung is indeed Ma Wanchang, then that change was likely to have been prompted by Ma's effort to enter the US in the name of another man who had been there before, and therefore make the whole process a lot easier."

Karen Ma, for her part, believes that the envelope had been prepared in both Chinese and English by his great-grandfather for Carpentier before he left the US in 1905, being the attentive helper he had always been. She has turned down all media interviews, citing the coronavirus pandemic and the need to focus on her family.

In one of his letters to the university president Seth Low in 1901, Carpentier said: "The identity of Dean Lung need not be questioned. He is not a myth but a very real person. And I would like to say of him that if, among people of humble birth and fortune I have ever known a born gentleman with all the inbred qualities essential to that character, not even excepting that rarest instinct never to give 'unintentional annoyance to others'-he is one."

Yet in the early 19th century such a man could find no place in US society, which had turned against all Chinese immigrants with hatred. In what is now regarded as the largest lynching in American history, an estimated 17 to 20 Chinese immigrants were hanged by a mob in Los Angeles on October 24, 1871.

In 1882, seven years after Dean Lung's arrival, the US Congress passed the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act, barring all Chinese laborers from entering the country. The act was renewed for another 10 years in 1892.

This means that every time before Dean Lung left for his home (He did this four times according to himself, including in 1905, after which he probably did not return), he had to prove that he was a man of means, which he was not, as pointed out by Carpentier while asking for "a life annuity "on his behalf. To testify, two white witnesses were needed, roles readily filled by Carpentier and a lawyer friend of his.

"I'm sure he endured a lot of hardship, and a lot of racism from people around him," says Mia Anderer, a daughter of Japanese immigrants whose father once struggled in his adopted home and was interned for years like all his fellow Japanese Americans after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 and war ensued.

"To me he's a courageous, enterprising and generous man who sought to foster greater understanding of the country and the culture from which he came."

In a letter to Carpentier in 1901, Low wrote:"As you say, the United States and China are likely to be more intimately connected than ever in the years to come … I can think of no better way of developing among our own people a correct knowledge of the Chinese than the way you have chosen."

It was also a way Dean Lung had chosen, at a time when the average monthly pay for an immigrant Chinese laborer was somewhere between $30 and $40.

Since April, Anderer has done several teleconferences with Karen Ma, in one of which the chairman of Columbia University's Department of East Asian Languages and Culture took part. Additional information was provided, although Karen asked Anderer "not to divulge any of it".

"The department chairman is inclined, as I am, to believe Karen Ma. But there's no public official reaction, as the university has bigger concerns right now about how to deal with COVID-19 and reopen," she said.

"Whether something is found or not, the story will stand on its own-just the story as it is," she said during an interview last year.

In that respect, perhaps nothing is more emotionally evocative and revealing than the way Dean Lung signed his brief letter of donation: "Dean Lung,'A Chinese Person.'"

zhaoxu@chinadailyusa.com